RISE DIGITAL LEARNING SERIES

Racism

Research shows that discrimination, like racism, has typically been better understood by those who have experienced it. As a result, many think that racism is a thing of the past. But unfortunately that's not the case. In the first topic of our digital learning series, we explore some of the relevant ways racism exists in our society and share personal stories from athletes and sports leaders who have experienced it firsthand.

When was the first time you recognized race as a social construct?

We asked athletes and sports leaders to share their personal experiences with race. Hear their stories as featured on our podcast and from "A Walk In their Shoes," an element of our Champions of Change fan experience.

"Racism is not about how you look, it is about how people assign meaning to how you look." — Robin D.G. Kelley

Caron Butler

NBA Legend

Kristen Ledlow

Turner Sports

Katrina Adams

USTA, Immediate Past President & Vice President, International Tennis Federation

Hear Katrina's full interview on Champions of Change: The RISE Podcast

Tell us your story.

Share the first time you recognized race as a social construct by tagging us @RISEtoWIN (Twitter/Instagram) or @RISEtoWIN (Facebook) and using the #LearnToRISE

RISE Perspectives

Racism in a pandemic: What we must not forget

By Dr. Andrew Mac Intosh

As we face the challenges of COVID-19, it's important to recognize that the virus has not impacted us all in the same way.

The advantages that many of us had going into this crisis have contributed to our resilience and the ways in which we have been able to respond. Conversely, those who have traditionally been marginalized in our society have had a more difficult time coping with the onset of the virus.

As we reflect on these concerns, we are reminded that more than ever, everyone needs to practice and utilize the skills of empathy, perspective taking and cultural competence. We need to stay vigilant and aware about the ways in which issues of racism and discrimination continue to impact us.

One major challenge around this pandemic has been a number of false, biased perceptions about the virus, such as the belief that Asians and Asian-Americans are more likely to have the virus or that African Americans/Black people cannot get it. Another misconception is that only older people should be concerned about COVID-19.

Quite simply, these statements are all not true. More pointedly, they are rooted in various forms of bias: racism, xenophobia and ageism.

While initial data does show that older people (along with people who have pre-existing health conditions) are more likely to have severe medical issues or die as a result of the virus, younger people are also susceptible to contracting and spreading the virus and experiencing severe symptoms. The outbreak of the coronavirus began in Wuhan, China, but it quickly became global, with major outbreaks across Europe and now the United States, impacting all people.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as well as the World Health Organization (WHO), confirmed there is no truth or validity to the belief that certain races or ethnicities are at a lower or higher risk of contracting the virus or recovering from it more quickly or easily. All persons are at risk. It is not possible to determine whether someone is more likely to have the virus based on their appearance or age and therefore wrong to target someone or assume they are infected based on their racial, ethnic or national identity. The dissemination of these false notions and rumors is harmful not only to those being discriminated against, but to our collective global efforts to combat the virus itself.

Even further, these views underscore the ways in which racism and other forms of discrimination intersect with the various institutions in our society.

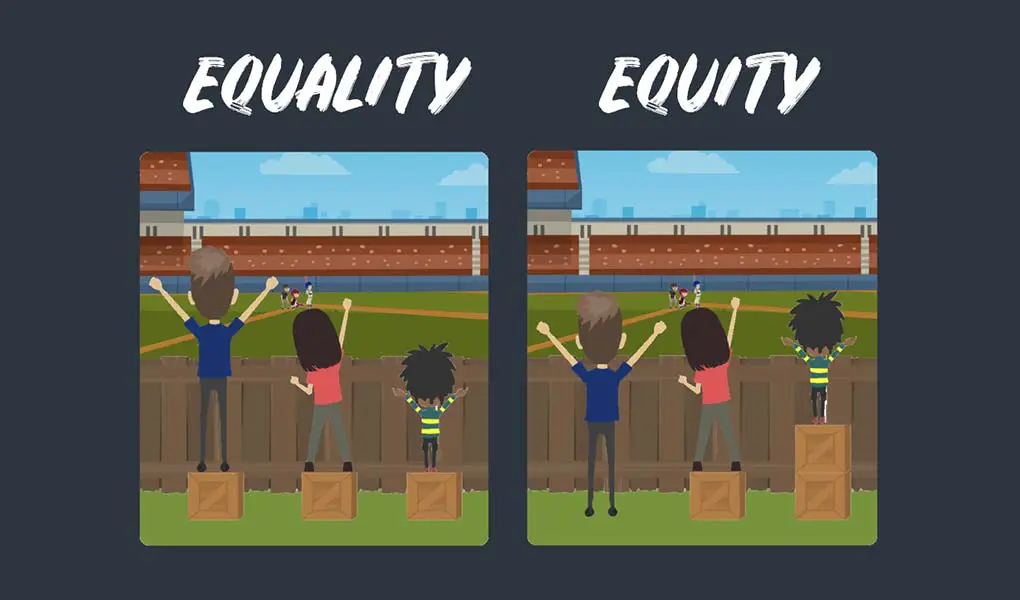

Historically, specific groups have had differential access to critical resources and this pandemic has only highlighted such issues of systemic racism.

Many people have lost their jobs or seen a reduction in income due to the economic downturn, as well as public instructions to stay home or avoid certain businesses. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics indicates that less than 30% of workers are able to work from home or telework, which means the ability to continue work from home and receive pay is a privilege not afforded to everyone.

Racial minorities will be more adversely impacted by these layoffs and unfortunately necessary shutdowns, given the way that race often intersects with socioeconomic status and the professions that people hold. Similarly, differential access to healthcare, insurance coverage and historically higher incidence of conditions like diabetes, heart disease and cancer, may make minorities a more vulnerable population given the current strain on our healthcare system.

The same is true in the education space. Many colleges have moved to virtual teaching to complete their semesters and K-12 institutions have provided digital and online resources to their students. Still, access to the internet is not the same for everyone across the country.

Rural and urban schools do not have the same types of internet speeds or the number of teachers who can support students while they are self-isolating. Data also shows that Blacks and Hispanics have less access to the internet than other racial groups. The Pew Research Center reported that while 82% of Whites have a computer at home, only 58% of Blacks and 57% of Hispanics could say the same.

This is undoubtedly a difficult time. As we deal with what is primarily a health crisis, we should challenge ourselves to exercise our cultural competence skills and foster greater inclusivity.

Understandably, we are physically isolating ourselves and turning inward during this time to support our families and loved ones. Still, this limits the time we have for getting to know one another better, and can unintentionally create and reinforce divides that already exist in our society.

At RISE, we use sports as a way to bring people together and teach about diversity concepts, while empowering athletes, students, executives and administrators with the skills to be leaders in addressing racism and promoting inclusion. One of the core principles of our work around diversity is that sharing more about ourselves can bring us closer together. As individuals, we foster understanding, inclusion and community by getting to know those around us better and creating a feeling of trust and sharing.

One thing I suggest we all do is to think about and discuss with someone else the ways in which our racial, ethnic and other identities have impacted the ways in which we have experienced this pandemic. Even as we face this crisis, we must ensure we are not perpetuating the inequities of our society, but instead are working to combat them.

Andrew Mac Intosh, Ph.D. holds degrees in Kinesiology, Applied Psychology and Sociology. As Vice President of Curriculum at RISE, he is responsible for the design, delivery and evaluation of RISE's leadership and cultural competency curriculum, which is administered to professional, collegiate and school-aged athletes, coaches and administrators throughout the country.

Learn More to Do More

Check out this activity on Inclusion, Exclusion and Racism from RISE's curriculum. Talk about a time you were included, and when you were excluded. Explore the connection between racism and experiences of inclusion and exclusion.

There are many aspects to racism that we can often take for granted and accept as 'normal'. We often look and call out overt and interpersonal acts of racism without giving thought to the more silent and insidious ways in which racism exists in our society. Recent calls for anti-racist work are rightly rooted in the attempt to correct our indifference and seeming comfort with social norms, organizations, and practices that empower whites at the expense of persons of color. Anti-Racism proposes that we cannot be bystanders in the fight against racism. We are either working to name it and address it or we are supporting it by our silence.

"In this country American means white. Everybody else has to hyphenate." — Toni Morrison

RISE Perspectives

We need a cure for how students of color are policed on campus

By Ashanti Callender

As schools open this fall, there are increasing concerns about how COVID-19 will impact students' quality of learning across the country.

But there is another infection that has existed on college campuses long before COVID-19, which also must be addressed: racism.

The past six months have allowed us time to reflect. We have had to come to terms with a pandemic and a great deal of uncertainty regarding many aspects of life, ranging from healthcare and the economy to education and sports. We've realized that in order to defeat the virus, everyone must do their part by following public health guidelines for the sake of themselves, their loved ones and their neighbors.

During this time, we've also had to reckon with racism in a way that has perhaps been unprecedented in the country. Despite the misconception that racism must be overt to exist, racism can manifest itself explicitly and implicitly. American policies, such as the Jim Crow Laws of the early 20th Century, the War on Crime and Law and Order policies enacted during the Johnson and Nixon presidencies and Reaganomics are evidence that racism can be written into our systems.

It is not enough for us to acknowledge racism only when it is blatant. We also must acknowledge that racism can be perpetuated subtly and systemically.

Police brutality and the over policing of communities of color has emerged as an important part of this discussion. While it sometimes raises its head in overt ways, like the recent shooting of Jacob Blake, over-policing of people of color is a more subtle, insidious form of racism that also needs to be combated.

I am drawn to the issue of policing on campuses because it is something that I have seen affect people in my community. The school to prison pipeline is a trend that pushes youth into prisons by criminalizing them through disciplinary practices.

Growing up in New York City and attending public school, I have been fortunate to attend schools out of my neighborhood. What struck me is that the schools I attended were more affluent, had less students of color and also had less police officers. However, in many other NYC public schools, there has been a shift to rely on law enforcement to maintain discipline in schools rather than the teachers and guidance counsellors who are trained to work with youth.

Placing law enforcement officers, who often lack training in youth development models and psychology, in contact with young students, allows fear to infiltrate spaces in which learning should be taking place. This can create many challenges based on the role that law enforcement should be playing in our society. How and when law enforcement engages with students, especially at this young age, needs to be more strategic and intentional.

From the time I graduated high school, I have been mindful of how my educational opportunities over the last 10 years enabled me to construct a path out of New York City. Many in my home community, who have similar backgrounds, were not able to attend college due to a lack of similar educational support. Now that I am in college, I finally see firsthand what people I have grown up with have been saying most of my life.

Although I have not had a Georgetown University police officer directly perpetuate racism towards me, I have seen it happen, I have heard the cases from my peers, and I was afraid that the same experiences I had been fortunate to avoid when I was in New York had now caught up to me in D.C.

I did not realize how much fear of having a negative encounter with the campus police department had impacted my education until the COVID-19 outbreak, and we were sent home from school. Immediately, I felt a sense of ease, and did significantly better academically once I was in what I consider a safer environment.

Just as COVID-19 impacts people differently, racism also has varying effects on students living and studying on their respective campuses. This is particularly true when we look at the policing of students of color on college campuses.

To address this and other issues of racism, it too requires everyone to do their part, no matter if you personally experience racism or not. Ultimately, like the COVID-19 virus, when thinking about racism on campus there are asymptomatic, presymptomatic, and symptomatic college students:

Asymptomatic Students

Asymptomatic students are aware that racism exists, but have never truly experienced it, either on campus or prior to their arrival. Still, they are part of a system that perpetuates racism and they cannot be considered anti-racist, or without the virus, until they hold the systems that sustain racism accountable. These students do not identify specific types of policing on their campus, for example, as a part of the problem with racism.

Presymptomatic Students

Presymptomatic students have been exposed to implicit and explicit biases before they arrived on campus. They remember their elementary school classrooms where the teacher asked the young Black student, "Can I touch your hair", and have seen store clerks cautiously follow Black shoppers down the aisles. Although this was a reality that presymptomatic students were used to, they expected that their new home on campus wouldn't exhibit such symptoms of racism. As semesters go on, their expectations are not met. After experiencing that, although racism on campus is not blatant, through the policing of black spaces, they realized that their campus home was not much different from the communities they left.

Symptomatic Students

Symptomatic students are those who are impacted by racism in ways that do not allow them to deny or ignore its existence. This group of students either needs to shrink from or push against the racism they experience. Those two options are all that are available once one becomes aware about the disease of racism. My approach has been to use my ability to inform and educate myself and others on the ways racism can permeate our campuses and the society more broadly. There are, however, other more direct strategies.

One such group of symptomatic students involved in more direct approaches are the organizers at The Georgetown University Against Police Aggression (GUAPA) organization. This group was formed by undergrads of color to help mitigate rising tensions fueled by accusations of feeling consistently over policed by the Georgetown University Police Department (GUPD).

Members of college communities, from students to professors, recognize that systemic racism is still evident, but it is not enough to just call out the issue, it is imperative to act on it as well. Toella Pliakas, lead organizer of GUAPA, says, "There is a difference between how students experience [policing] on campus and how Georgetown's police department interprets their own policing."

After its founding, GUAPA initiated conversations with the GUPD to together implement the following changes: affirming a commitment not to arm GUPD, and working to keep the Metropolitan Police Department off campus.

Perhaps their greatest achievement, however, was the creation of a Bias Form on the GUPD website so that complaints of prejudiced policing could be openly reported. When thinking about changing police dynamics and the balance of power they traditionally possess, it is hard to do that without mechanisms for students and other members of campus to report concerns and breaches of authority. Often, a lack of reporting stems from fear of, as well as concerns that your experiences will not be taken seriously. This form provided a transparent mechanism for accountability.

Collectively, these measures represented significant progress and demonstrate the ability of student-led advocacy to make a real difference. But while these policies and continued dialogue have sparked change, continued efforts on behalf of students and law enforcement are required to achieve truly equitable policing systems. What is required is engagement by all at the university to engage in the necessary conversations and action steps to uproot it. As Dr. Ibram X. Kendi alludes to in his work, one is either actively combatting racism (anti-racist) or is supporting racist systems, policies and practices.

To be anti-racist, we have to step outside of ourselves and understand that even if a situation does not directly impact us, it doesn't mean it is not impacting someone else. Being anti-racist calls for us to have empathy towards those that have been impacted by racism; explicitly and implicitly. It is only such an approach that will allow us to help end racism systematically in our society.

The Big East's partnership with RISE has been formed to address the systematic barriers, biases, and anti-racist solutions that can be taken by leaders on campuses. I think this is a perfect opportunity for the Georgetown Athletics Department to use their platform to share the knowledge that comes from the leadership workshops and the perspectives shared in their immediate cohort to help facilitate a greater conversation with the University, holding them accountable to their duty to make the campus safe for ALL students. It is a step in the right direction that a sector of the University has taken the initiative to move beyond understanding that racism exists to developing anti-racist action items. However, it is not enough for only one department to be equipped with these tools. Now that the torch is in the Georgetown Athletics Department hands, I encourage them to use what they will be learning over the next two years and have learned through previous efforts in this space with other departments to not only address racism but to challenge the over-policing of students of color on our predominantly white campus. Only when an institution combats racism on all fronts can they call themselves a safe space for all students.

Let's be clear. Racism is a disease. And when we talk about combatting it in the collegiate space, it is not enough to simply acknowledge the racist past of your institution, which many have done. To fully cure what has been ingrained in the soil that thousands of students walk on each year is to collectively work to dismantle and rebuild the systems that uphold racism.

Ashanti Callender is a student at Georgetown University, Class of 2021, and a member of RISE's Summer Intern class of 2020.

College Athletes Pledge to Be Anti-Racist

Student-Athletes from institutions across the country take the RISE Pledge to End Racism and commit to ways they can be anti-racist on their campuses, in their teams and alongside their peers. Join them and take the RISE Pledge to End Racism.

How to be anti-racist

Are you able to recognize opportunities to be anti-racist? Do you notice the ways society treats people of color and minorities unfairly? Can you spot microaggressions and the impact of racism when they're directed at others? Explore this activity to learn and reflect on what it takes to be anti-racist.

Go to ActivityRISE Critical Conversation: College Athletes talk Anti-Racism

College athletes from across the country join RISE to talk about anti-racism on their campuses and in their athletic programs, and discuss what they believe needs to be done to advance racial equity and social justice.

Our

Partners

Stay

In Touch

Follow us on social media.