RISE DIGITAL LEARNING SERIES

Empathy

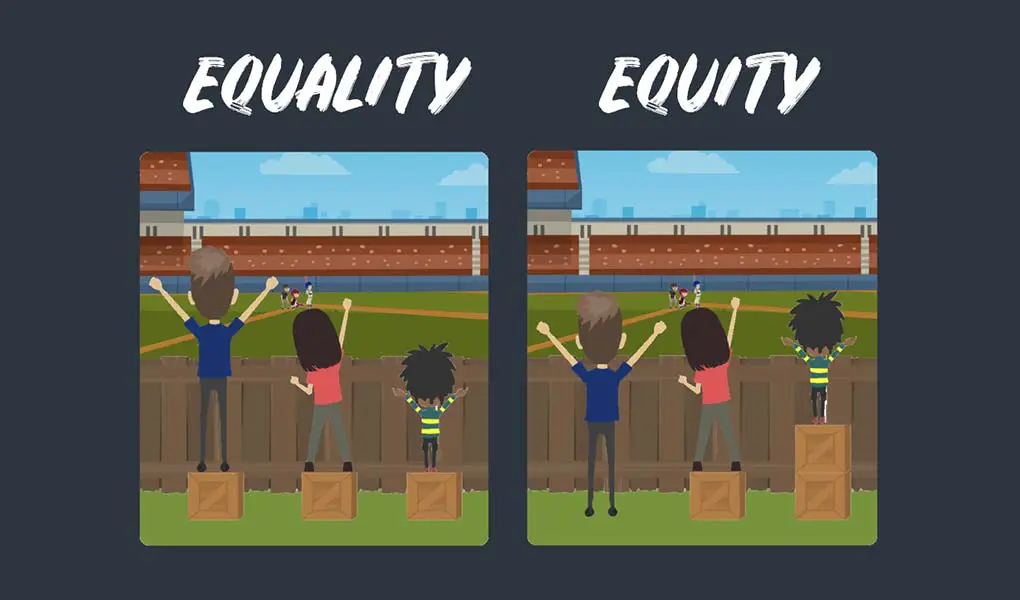

Empathy is important because it allows us to connect with each other and build understanding that can change our perspective and open our eyes to the experiences of others. These shifts are critical to improving race relations and addressing inequality.

There is an important distinction between empathy and sympathy. Sympathy is defined as a feeling of pity and sorrow for someone else's misfortune. It is simply caring that somebody is in pain or suffering. Empathy goes beyond that and involves a deeper connection with someone. Empathy is defined as the experience of understanding another person's condition from their perspective. It refers to the ability to feel or emotionally relate to another person's pain and suffering. When allies in the fight for racial equity have empathy for persons of color, they better understand the issues are therefore more personally invested and equipped to take action.

"One doesn't have to operate with great malice to do great harm. The absence of empathy and understanding are sufficient." — Charles M. Blow

RISE Perspective

My Heart is with you, My Pain is for you

By Madeline Bachelier

For the past couple of weeks, I have woken up each morning feeling heavy.

My thoughts and emotions have spiraled seeing the amount of information, resources, and support sparked from the recent deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd. I see and feel the amount of energy. The pure energy of limitless work to demand accountability for police brutality, elevate the movement and voices of Black Lives Matter and further educate ourselves on issues that continue to steal the opportunities and lives of innocent people.

I am a Mexican-American woman who grew up learning two cultures, two languages, and practically two different ways of life. Although a person of color, my experiences dealing with implicit bias, microaggressions, prejudice and racism do not compare to the daily challenges my Black friends and peers endure.

Knowing that, my tears and heavy chest left me thinking, "Why am I grieving so much? Why are my emotions at an all-time high with anger and frustration?"

At the time I did not realize that the pain and frustrations I felt were moments of empathy. Truthfully, as a way to make sense of all this, I thought my emotions were inappropriate and that I should channel that energy into action.

But then I read this piece from Morgan Harper Nichols, writer, musician, and artist who eloquently expressed empathy as:

Let me hold the door for you.

I may have never walked

A mile in your shoes,

But I can see that

Your soles are worn

And your strength is torn

Under the weight of a story

I have never lived before.

So let me hold the door for you.

After all you've walked through,

It's the least I can do. – Morgan Harper Nichols

As I processed the news each day, seeing protestors take to the streets throughout the nation, and listen to the challenges my friends and colleagues have been facing, I could not help but think how much empathy reveals who we are as people.

Empathy says, "I see you, and I feel for you." Empathy is the first step to connection, and has no bounds in its ability to shift behaviors and convey a collective sense of support that stretches beyond all limits.

When we think about practicing empathy what comes to mind? In most cases, empathy does not always have to look the same across different situations or be expressed to the same degree. It is important to think of empathy through other acts of appreciation, as well.

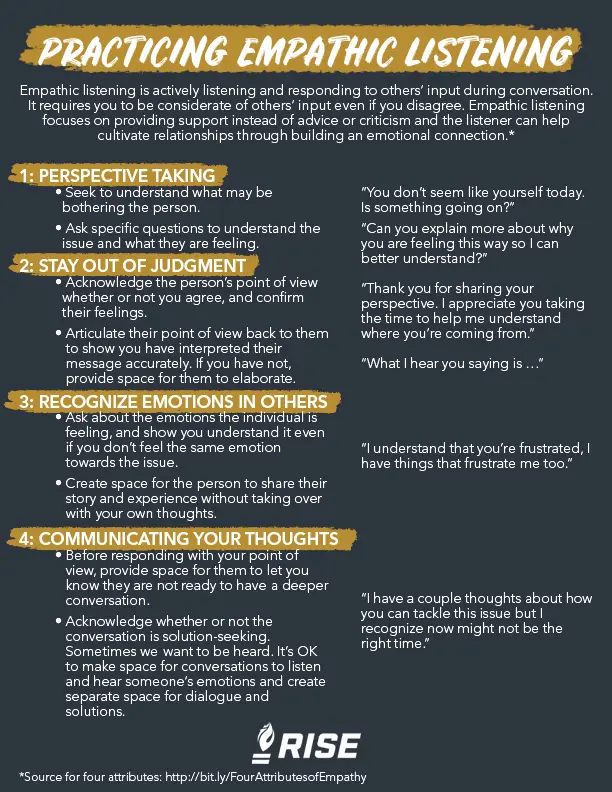

RISE teaches four skills to empathy, introduced by Dr. Brené Brown:

- Perspective Taking

- Staying out of judgement

- Recognizing emotions in others

- Communication to others that you recognize their emotion

We may not always fully understand what someone is going through, but we can first try to connect with them through practicing these four skills. If at one point you also experienced the same feeling but not necessarily in the same situation, that in a sense is building empathy.

Empathy leads to education, and until you expose yourself to different perspectives and experiences that may challenge your privilege and how you use it, you may just live in a comfort zone that simply expresses sympathy, but never really leads to action.

A study published by the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley suggests, "cognitive empathy," or knowing how another person feels and thinks is not enough to inspire action. What does is, ‘'emotional empathy," which urges feeling the same emotions of other people as if they are your own.

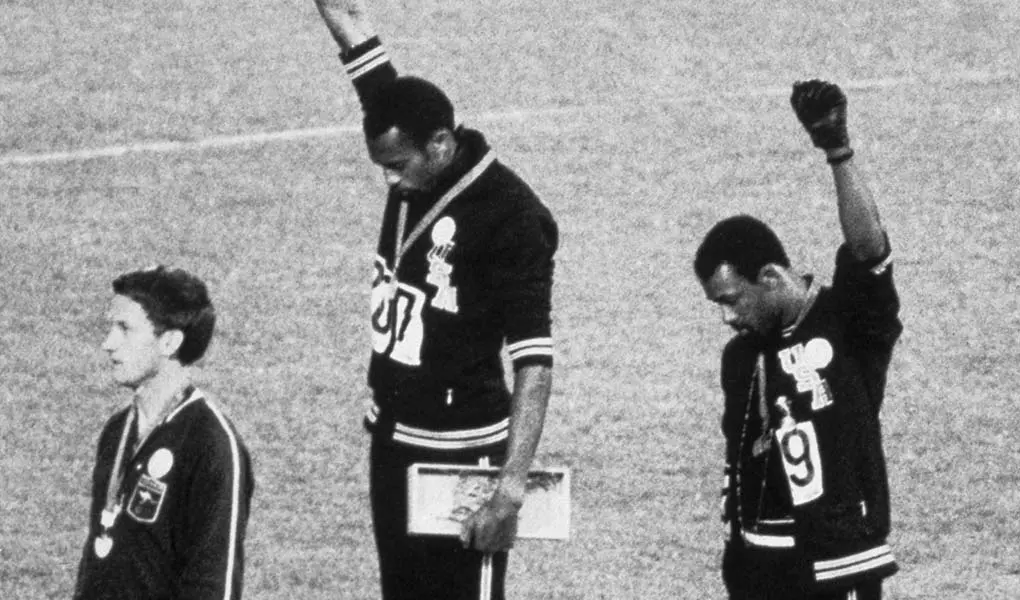

For years, athletes have evoked and expressed different forms of empathy through their activism as a way to raise awareness around important social justice issues.

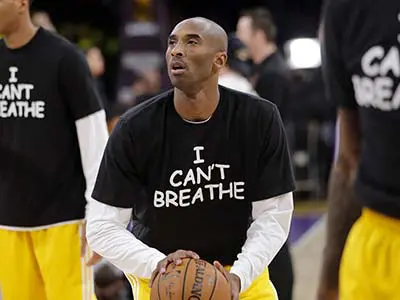

In 2014, for example, NBA stars such as LeBron James, Derrick Rose, and Kobe Bryant wore "I Can't Breathe" T-shirts during warm-ups to raise awareness of police brutality following the killing of Eric Garner in New York. Social media posts of athletes wearing these shirts have resurfaced in light of Floyd's murder, and athletes like James and countless others continue to speak out on matters of race and social justice.

Nationwide movements cannot grow with only those directly impacted by the cause. They require diverse support and a coalition of people and groups. That, is built with empathy. It's empathy that compels people to fight for the plights of others and sparks momentum to address critical social issues. Athletes wearing "I Can't Breathe" t-shirts or sharing their personal stories puts a human voice and face on the fight against racism and police brutality, and helps those who may not be personally impacted by those issues connect to the cause.

But one doesn't need a national platform to build or evoke empathy. In your own school, community or office (virtual or in-person), anyone can be a leader in this space.

Diversity and inclusion expert, Dr. Janice Gassam (2018) lists different tactics for leaders to build empathy in and out of the workplace:

- Listen. Research indicates that listening to other people from different walks of life talk about their experiences and journey through life, difficulties, hardships, and triumphs can impact our empathy levels.

- Slow Down. Listening is very important, but unless we slow down and stop multi-tasking, it is difficult to really hear the differing experiences of others.

- Be Curious. Individuals that are more curious tend to also be more empathetic. Make a concerted effort to interact with people who are different than you, and take time to learn about their stories. Don't be afraid to ask questions. Asking questions allows the other person to feel like their voice is heard and valued.

- Volunteer. The act of volunteering may actually increase our empathy levels. Organizations should incorporate volunteering opportunities into the corporate structure to allow employees to feel like they are making a difference and impact.

The purpose behind practicing empathy can mean working towards a common goal. At RISE, we recognize starting with empathy opens up conversations that build trust and confidence. Moreover, empathy reaches a level of connection that we often strive for within our relationships with family, friends, and our community.

For me, showing vulnerability and empathy towards someone and the struggles they face reveals another kind of understanding. The kind that screams, my heart is with you, my pain for you, and I am motivated to advocate for you.

Madeline Bachelier is Manager, Partnerships at RISE. In this role, she works to expand RISE's relations with college athletic departments and professional teams, and helps seek new opportunities to empower the sports community to be leaders on matters of race relations, diversity and inclusion. She holds a Bachelor's Degree in Marketing from the University of Arizona.

Sport, Empathy & Law Enforcement: A RISE Critical Conversation

Watch as top athletes and police officers from around the country discuss empathy and law enforcement and how sport can play a role in bringing communities together. Moderated by Bonnie Bernstein, the conversation features:

- Renee Montgomery, 2x WNBA Champion

- Jaiden Lars-Woodbey, Florida State Football Student-Athlete

- Officer Luis Crespo, Chicago PD

- Officer Shannon Finis, Charlotte-Mecklenburg PD

- Officer Michael Richardson, Detroit PD

Empathy vs. Sympathy

Dr Brené Brown reminds us that empathy for others is only possible if we are brave enough to really get in touch with our own feelings.

Perspective Taking

One of the key skills of practicing empathy is perspective taking. Perspective taking is the process through which one is able to see the viewpoint of another, understanding their feelings, intentions, thoughts or view of a particular situation. Watch this video to learn more about perspective taking.

Complete this activity to learn more about empathy.

Go to ActivityLearn More to Do More

Explore the difference between sympathy and empathy and recognize and practice the difference between problem solving and empathetic listening in our "Practicing Empathy" activity.

In course 1, we made the important distinction between empathy and sympathy. Sympathy is defined as a feeling of pity and sorrow for someone else's misfortune. It is simply caring that somebody is in pain or suffering. Empathy goes beyond that and involves a deeper connection. Empathy is defined as the experience of understanding another person's condition from their perspective. It refers to the ability to feel or emotionally relate to another person's pain and suffering. Empathy allows us to connect with each other and build understanding that can change our perspective and open our eyes to the experiences of others. These shifts are critical to improving race relations and addressing inequality. In course 2, we examine what empathy looks like as others put it into practice. We challenge all of us to consider using empathy more as we navigate the world. While a hard task, it can help us foster and build connection when there is currently so much division.

"Opinion is really the lowest form of human knowledge. It requires no accountability, no understanding. The highest form of knowledge… is empathy, for it requires us to suspend our egos and live in another's world. It requires profound purpose larger than the self kind of understanding." — Bill Bullard

Educate

Too often when we make mistakes, we allow shame and our ego to drive us to double down, refusing to consider the hurt or challenges our actions may have created.

In this personal essay, Kyle Larson reflects on his experiences since using a racial slur in March. In it, he shares some of the many important lessons that he took away from that moment. He talks about his ignorance, personal growth and accountability. One of the most important things he shares via his piece is perhaps not discussed as explicitly. Kyle shares and exemplifies the skill of empathy and perspective taking, as he engages a wide range of persons and tries to understand their perspectives. His personal journey serves as a great example of the work and reflection necessary as we have tough conversations about race, racism and diversity and inclusion more broadly.

RISE Perspective

Kyle Larson: My Lessons Learned

By Kyle Larson

Back in June, two days before the NASCAR doubleheader weekend at Pocono Raceway, I found myself less than 100 miles away in a classroom in Philadelphia. Although the track was a short drive north up I-476, I wouldn't be going in that direction. It might as well have been on the moon.

Ten weeks earlier, I had said the N-word on a public channel before an esports race. In an instant, my career was shattered. I was rightly suspended by NASCAR and fired from my job with a top-tier team. I jeopardized the livelihoods of the crew members who had poured their careers into building me fast racecars. My fans were upset. In an instant, I turned a lot of lives upside down and destroyed my own reputation.

Anyone who has massively let people down knows what the worst part of all this is. As I sat in that classroom, less than two hours from my previous, comfortable life, I looked across at a group of people who had once supported me and were now completely and totally disappointed.

I was at the Urban Youth Racing School, which exposes kids – many of whom are Black – to opportunities in motorsports. I had visited the school a few times in the past, spoken with students, hosted them at the track and attended a few of their end-of-year awards ceremonies. I loved their work and stayed in contact. I was running a sprint car – the only type of racing I've been able to do – down the road in Harrisburg, so I made the three-hour drive to Philly to reconnect with the owners, Anthony and Michelle Martin, and one of their students, Jysir.

Last October, Jysir celebrated with me and my team in victory lane when I won the NASCAR race at Dover. He was one of the many people I'd hurt, and he wanted to know why this happened. So did his mom. And they didn't just want to hear it from me over the phone or on a Zoom call. It needed to be face-to-face. I was honest with them. We talked about difficult subjects for more than two hours, and I spent a lot of time listening. Michelle educated me on the journey of Black people in America and the ugly history of racism and derogatory slurs. I offered my apologies to Jysir, his mom and the Martins for the pain I caused. Instead of the anger I expected, what I got in return was empathy.

I'll tell you what I told them.

On the night of Sunday, April 12, 2020, when the sports world was stopped because of the pandemic, I said the N-word over a microphone before an online race. Did I know the whole world could hear me in that moment? No, I did not – I thought it was a private channel. So when I tell people that I wasn't in the habit of saying the word and they roll their eyes in response, I don't blame them. I get it.

Auto racing is my passion. During the NASCAR off-season, I've sometimes competed overseas. On one of these trips, I was around a group that used the N-word casually, almost like a greeting. Of course, it doesn't matter where this happened, how the word was used or what the people around me did. The fact is that the word was said in my presence and I allowed it to happen unchecked. I was ignorant enough to think it was OK, and on the night of the esports event, I used the word similarly to how I'd heard it. As I write this, I realize how ridiculous, horrible and insensitive it all sounds.

And what makes it even worse is that I truly do know better.

I'm half Japanese. My parents are an interracial couple who have gotten disapproving stares and been made to feel uncomfortable just for being together. And all of a sudden, they were being asked why their 27-year-old Asian-American son said something racist. My maternal grandparents were held in an internment camp during World War II. There's absolutely no excuse for my ignorance.

My mom and dad's disappointment really affected me. Trust me when I say that they did not raise my sister and I this way. But even though I let them down in a particularly hurtful manner, they still supported me when I most needed them. I was, and will always be, grateful for how they've helped me navigate the last five months of my life.

But as much as my parents have always believed in me, there's no one who holds me to a higher standard than I do. And I had failed. I wanted to hide. I shut down my social media accounts. In the time of COVID-19, wearing a mask in public actually made me feel more comfortable. It wasn't healthy at all. I needed to take back control.

Since April, I've done a lot of reflecting. I realized how little I really knew about the African-American experience in this country and racism in general. Educating myself is something I should've done a long time ago, because it would've made me a better person – the kind of person who doesn't casually throw around an awful, racist word. The kind who makes an effort to understand the hate and oppression it symbolizes and the depth of pain it has caused Black people throughout history and still to this day. It was past time for me to shut up, listen and learn.

The first lesson: The N-word is not mine to use. It cannot be part of my vocabulary. The history of the word is connected to slavery, injustice and trauma that is deep and has gone on for far too long. I truly didn't say the word with the intention of degrading or demeaning another person, but my ignorance ended up insulting an entire community of people who, in the year 2020, still have to fight for justice and equality. When I look back at these last few months and see all the protests and unrest in our country, and the pain Black people are going through, it hurts to know that what I said contributed to that pain.

NASCAR has a zero-tolerance policy on this type of behavior. When they suspended me, I received a plan that started with mandatory sensitivity training and went from there. I'm in regular contact with them, and I've learned and grown as I've gone through the program. I hope to race in NASCAR again.

But I also needed to do some work on my own, so I hired a diversity coach, Doug Harris of The Kaleidoscope Group. There's no B.S. with Doug. He gives it to you straight, even if it's uncomfortable. He is a Black man with seven kids, and the conversations he has to have with them about things like driving around town and interacting with police when they're pulled over – not if they're pulled over, but when – gave me a level of awareness I hadn't had before, but it also made me realize the kind of privilege I've taken for granted. I mean, my livelihood is literally driving. Everyone should have someone in their life who will talk to them like Doug talks to me.

In early May, I traveled to Minnesota and volunteered in a food drive organized by Tony Sanneh, a retired pro soccer player who has his own charitable foundation. After the death of George Floyd, I went back to Minneapolis and joined Tony and his leadership team at the memorial that had been set up. We went around to areas of the community that had been affected. I asked them why people would destroy their own neighborhoods. Their response was eye-opening: "When people haven't been accepted by their community, they don't have any attachment to it."

I spoke with Olympic legend Jackie Joyner-Kersee and toured her community center in St. Louis. I've had conversations with Black athletes like Harold Varner III, racecar drivers like Bubba Wallace, J.R. Todd and Willy T. Ribbs, and corporate executives like Kevin Liles (formerly of Def Jam) and Perry Stuckey (of Eastman). We didn't just talk about the Black experience – we discussed the importance of having empathy and considering the struggles of people who don't look like me.

In all these experiences and conversations, there's been a common and unexpected response. Everyone I've talked to was fully aware of the mistake I made and they still chose to invest their time and energy into my growth as a person. Don't get me wrong, these have not been easy conversations. One of the toughest I had was with Mike Metcalf, an African-American crew member who was on my NASCAR team for many years. I've worked with Mike since I started in NASCAR, and disappointing him was the same as letting down family.

I've received a lot of straight talk from Mike and others since April. But what gives me hope and humbles me is how so many people have opened their doors to lift up someone who probably doesn't deserve it and to share perspectives I should've sought on my own a long time ago.

After I said the N-word, anger came at me from all angles. Being labeled a racist has hurt the most, but I brought that on myself. What I didn't expect, though, were all the people who, despite their disappointment in what I did, made the choice to not give up on me. It motivates me to repay their faith by working harder, not giving up on myself, and making sure something positive comes from the harm I caused.

For far too long, I was a part of a problem that's much larger than me. I fully admit that losing my job and being publicly humiliated was how I came to understand this. But in the aftermath, I realized that my young kids will one day be old enough to learn about what their daddy said. I can't go back and change it, but I can control what happens from here on out.

I want them to know that words do matter. Apologizing for your mistakes matters. Accountability matters. Forgiveness matters. Treating others with respect matters. I will not stop listening and learning, but for me now, it's about action – doing the right things, being a part of the solution and writing a new chapter that my children will be proud to read.

People have taught me a lot over the last five months. The next time I'm in a classroom, I hope I can repay their kindness by sharing my story so others can learn from my mistakes. Making it a story I'm proud to tell is completely up to me.

Inspire

During a RISE Critical Conversation earlier this year, Florida State football player Jaiden Lars-Woodbey, Chicago police officer Luis Crespo and Detroit police officer Michael Richardson provide an example of empathic dialogue as they discuss walking in each other's shoes and understanding one another's perspectives.

Act

Our

Partners

Stay

In Touch

Follow us on social media.