RISE DIGITAL LEARNING SERIES

Bias

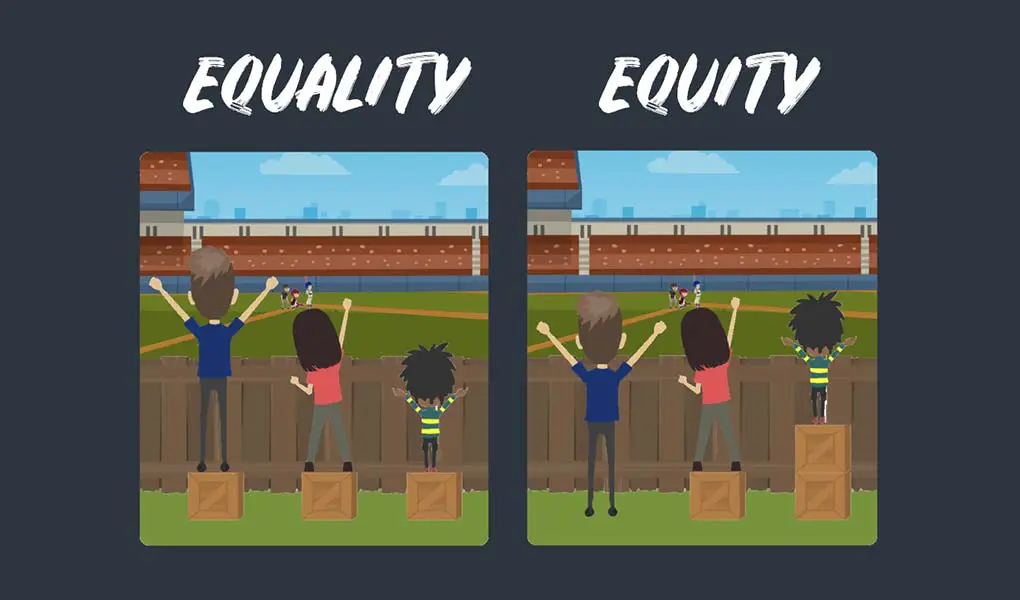

This week, the RISE Digital Learning Series will explore the concept of bias. We have "bias" when we have a preference or an aversion to something, someone or a group of people, as opposed to being neutral. Some biases are positive and helpful — like choosing to only eat healthy foods. However, rather than basing our preferences on actual knowledge of an individual, group or circumstance, biases are often based on stereotypes. These stereotypes may be about socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity or educational background, for example. Because these preferences or aversions are based on preconceived opinions and not in reason or actual experiences, they tend to be unfair, illogical and inaccurate. Further, they can lead to rash decisions or discriminatory practices. At the individual level, for example, bias can negatively impact someone's personal and professional relationships; at a societal level, it can lead to unfair persecution of a group, such as the Holocaust and slavery. This week, we will examine different types of bias in society and the ways we might begin to change them.

"There is no neutrality. There is only greater or lesser awareness of one's bias." — Phyllis Rose

RISE Perspectives

Implicit Bias: Why Police Brutality is a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

By Samantha Rosette

We all have preconceptions and biases, but they become dangerous when they detrimentally affect the way we treat one another.

RISE defines bias as "being in favor of or against one thing/person/group compared to another, usually in a way considered to be unfair." While we all have biases, the danger is that biases are not necessarily based on fact, but rather, are inferences we make about the world.

When we are biased, we generalize the ideas, opinions and thoughts we have to groups of things (people, animals, food) rather than limiting them to those with which we have had experience. In other words, we become comfortable with the things, places, and people that are similar to those we regularly interact with, and anything or anyone that differs from that is instinctively met with a sense of caution, suspicion, and sometimes even fear.

There are many ways through which bias manifests itself in our society. Not only can people hold biases about different things such as gender, race, sexual orientation and age, but bias can also operate at implicit, individual and systemic levels. A recent incident in Central Park in New York (see below) illustrates differing levels of bias and how they can operate in tandem. In the incident, Amy Cooper, a White woman walking her dog, calls the police on a Black man who asks her to put her dog on a leash. The incident resulted in Cooper calling the police, claiming she was being threatened by an African American man. The video recorded by the man does not support her claims.

This incident demonstrates that whether Cooper herself was biased toward African American men, she understood that that bias existed in the society and she was willing to use that against the man because of his race and how he would be unfairly perceived.

There was conscious, interpersonal bias, since at a surface level, Cooper displayed discomfort or disdain at being challenged and recorded by a Black man while they were alone in the park. Whether it is racially motivated or not, Cooper’s behavior suggests that this man has no right to speak to her to correct her behavior.

There was also structural and systemic bias since Amy Cooper calls the police and identifies the man, Christian Cooper, as an "African American" male knowing what image that would convey. Her call, and the words she used, were specifically engineered to "weaponize" the color of this man’s skin against him by her repeated reference to his race.

Finally, there was implicit bias. This type of bias is described by the The Kirwan Institute as, "the attitudes or stereotypes that affect our understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner". In making her call to the police, describing her threat and using the words African American male, Amy Cooper is hoping to leverage their implicit biases about black males in society. This form of bias though implicit can often lead to deadly consequences. The police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor are the most recent, tragic reminders.

In Minneapolis alone, a city with a 59% White population, police have used force against Black Americans at a rate of seven times higher than their White counterparts in the last five years (Oppel & Gamio). The same is true on a larger scale within the United States, home to a 70% White population, in which 3.5% Black Americans have reported having been subject to the use of nonfatal force by police, as opposed to just 1.4% of White Americans (U.S. Justice Dept.).

These disproportionate rates of police brutality against people of color suggest that the same implicit biases displayed by Amy Cooper are also prevalent within the law enforcement community. They are more likely to use excessive force in altercations involving people of color. This is likely a product of both the dangerous stereotypes about Black and Brown people, as well as a sense of White superiority within the U.S.

The first step in addressing implicit biases is to recognize and identify them. Because these stereotypes are so deeply embedded in American culture, it has been passed down and learned through subtleties of conversation. For example, White, wealthy people calling inner city areas home to high concentrations of people of color "bad neighborhoods," or telling their kids to "stay away from those parts," reinforces negative stereotypes about people of color and a sense of white superiority. Police officers, like the rest of America, have been raised on these stereotypes, so many have biases, implicit or not, to be increasingly fearful and "defensive" in situations involving people of color, making them quicker to use force, or shoot. The excessive use of force by police officers, therefore, works to maintain this sense of "superiority" that has been woven into the fabric of our country since Africans were brought here on slave ships and is continued through our current policies disproportionately disadvantaging people of color. The combination of fear and a sense of white superiority results in increased brutality, and the unnecessary deaths of Black and Brown people at the hands of police.

At RISE, specifically through our program Building Bridges Through Basketball, we use the unifying power of sport to form partnerships between law enforcement and the communities they are intended to serve. We work to break down systemic barriers, build trust between predominantly Black and Brown communities and law enforcement, and help them become more aware of their biases and how to prevent them.

I challenge you to practice perspective taking and to delve deeper in understanding where your biases come from and why they exist. I challenge you to hold yourself accountable and to acknowledge and retract your biases when you notice yourself thinking or acting on them. And finally, I challenge you to hold others accountable as well. While we cannot erase our country’s history of prejudice, discrimination, bias, and its perpetuation of police brutality, we can write a new future, and it starts with how we think about and treat each other, especially when we look differently.

Samantha Rosette is a native of The Bronx with an undergraduate degree from The University of Virginia in Education majoring in Kinesiology, and is currently a graduate student at Villanova University getting her Master's of Public Administration. She is a leader on the Villanova Women's Soccer team and a RISE 2020 Leadership and Education summer Intern.

Bias and Racism

Racism is Real

In this video we learn about the various ways in which racism still manifests itself in our society. The video show that bias, whether or not we are aware of it, results in a systemic pattern of discrimination. This pattern, in which white people generally have better outcomes and experiences as they interface with institutions in our society is known as systemic or structural racism.

Central Park Incident

A recently popularized incident in Central Park in New York illustrates differing levels of bias and how they can operate in tandem. In the incident, Amy Cooper, a White woman walking her dog, calls the police on a Black man who asks her to put her dog on a leash. The incident resulted in Ms. Cooper calling the police claiming she was being threatened by an African American man. The video recorded by the man does not support her claims. This incident demonstrates that whether Amy herself was biased toward African American men, she understood that that bias existed in society and she was willing to use that against him because of his race - first as a threat to the man who corrected her and then by following through on that threat.

"The Rooney Rule"

Jim Rooney of the Pittsburgh Steelers and N. Jeremi Duru of the Fritz Pollard Alliance and American University join Champions of Change: The RISE Podcast to talk about the NFL's Rooney Rule that requires teams to interview minority candidates for head coach and other top leadership positions, and why it's important to address bias in the hiring process to combat racism and create a more inclusive environment.

Learn More to Do More

Connect with friends and family and check out our "Understanding Our Identities" module. Explore labels central to our identities and think about how they not only affect our biases towards others, but others biases towards us.

As we discussed in Course 1, we have "bias" when we have a preference or an aversion to something, someone or a group of people, as opposed to being neutral. Some biases are positive and helpful — like choosing to only eat healthy foods. However, rather than basing our preferences on actual knowledge of an individual, group or circumstance, biases are often based on stereotypes. These stereotypes may be about socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity or educational background, for example. Because these preferences or aversions are based on preconceived opinions and not in reason or actual experiences, they tend to be unfair, illogical and inaccurate. Further, they can lead to rash decisions or discriminatory practices. At the individual level, for example, bias can negatively impact someone's personal and professional relationships; at a systemic and societal level, it can lead to unfair persecution of a group, such as the Holocaust and slavery. This is important to consider since our current push to dismantle systems of racism in the country requires us to individually consider, reflect upon and question the individual biases we hold while simultaneously challenging structures and institutions that have historically been biased.

"We can at least try to understand our own motives, passions, and prejudices, so as to be conscious of what we are doing when we appeal to those of others. This is very difficult, because our own prejudice and emotional bias always seems to us so rational." — T.S. Eliot

RISE Perspectives

Confronting my personal biases

By Peyton Finley

Working for RISE has impacted me personally in a lot of ways. I love the work we do and the mission I get to strive for every day. I feel so fortunate that I not only get to have job satisfaction in the work RISE does but also have the opportunity to learn and grow as a person every single day because of my incredible colleagues and the work they do.

I believe we are always learning, growing and changing as people. No one is a finished product. To think that I have lived and am living my life completely bias-free, fair and equal would be ignorant. I've made comments I wish I could take back and learned from past mistakes when I didn't know any better but was shown grace by my peers. I'm challenged to think with a new perspective and consider how those around me might feel differently.

One area I consistently find myself thinking and learning about is bias. Bias is a core concept we teach at RISE. It's a feeling, thought or inclination that is usually unreasonable or not well thought out. Biases tend to be illogical or inaccurate and are problematic because they don't allow the person bearing the bias to take all the facts or evidence into account when making a decision.

We are instinctually judgmental. It's a survival tactic. Is this going to harm me? Anger me? Harm others? Unfortunately, there are a lot of instincts and judgements that form over time through biases and stereotypes that we don't recognize they're not fair or false. But they've existed so long in our minds, we react without thinking about it. I once heard someone say "We can't control our first thought, but we can control our second thought and our first action." In order to take control of my second thought and first action, I have to recognize the problem with my first thought.

I grew up in a small, southern town for 21 years. My parents have lived in the same house as long as I've been alive, and I went to college not too far from home. The same things, people and values have surrounded me most of my life. It didn't really strike me what I was missing out on until I moved away and realized how much of the world I'd been unaware of. Growing up, most of the kids in my classes looked like me. The teammates on my soccer team, the dancers in my dance class, the friends I spent time with. I didn't even know more than one religion existed until studying it briefly in middle school.

While this might be seen as a safe and comfortable environment, it made me curious and eager to learn more once I knew more was available. It also inhibited me from understanding other people who didn't look or think like me. I learned, much too late in life, about the oppressions and microaggressions facing my peers that I never acknowledged. It now makes for some embarrassing and uncomfortable conversations, but I am so grateful to be given the opportunity to learn and grow.

I was challenged to think more deeply about my biases almost immediately after I moved to New York. I lived in a sublet in Harlem my first six months. My best friend lived in SoHo, and we planned to move in together once her lease ended. Being in a major city for the first time in my life, I experienced more anxiousness than ever before. It took some time to become accustomed to a very different lifestyle and being surrounded by so many cultures and experiences. It was frankly, a lot of mental and emotional stimulation.

As I became more comfortable, however, I started to realize that I was extremely comfortable walking to my friend's apartment in SoHo, a predominantly white and high-income area of the city, but more alert when walking to my apartment in Harlem, a predominantly Black area of the city. I realized the stark difference in my emotion when I left my friend's apartment late one evening after watching a show together.

As I walked to the Subway station near her apartment, I remember feeling happy as children rode bikes, shop owners brought their flower arrangements inside and customers rushed out of the local grocery store with bags full of groceries. The weather was perfect, it was almost the weekend and I was really starting to understand and enjoy the city. After the 30-minute ride from Spring Street to the 135th St Station, I began the short walk to my apartment. It was busy and loud for it to be 10 p.m. on a school night, and I recall feeling nervous. I turned the music down on my headphones so I could hear what was going on around me as my parents' voices rang in my head about the dangers of walking and listening to music.

As I waited to cross a street, I paused my music and stopped to think. What about my current surroundings were causing me to be more anxious than I was 30 minutes ago? Sure, Harlem had higher crime rates than SoHo. But had I ever experienced a crime here? No. Sure, Harlem was busier than SoHo right now, but hadn't it been busy like this since I moved here? Yes. It didn't take a lot of reflection to recognize that I was a minority in the area. What about that made me feel like I had to be more alert?

Simply it was that 23 years of learning through television shows and movies that predominantly Black areas are dangerous and predominantly Black communities mean I'm more likely to experience crime. Twenty-three years of being told to avoid a certain area of town or labeling a neighborhood as a "bad neighborhood." Twenty-three years of peers choosing to go to a certain restaurant or sporting event over another because it was less likely to get rowdy or for someone to get in trouble. Over time, even well-intentioned biases can become ingrained in our instinctual responses to a point of not even realizing why they are there or who they hurt.

I'll be honest – I didn't have that light-bulb moment and as a result all my biases went away. I'm still challenging myself every day to reflect on my thoughts. Is a thought I have in reaction to a moment reflective of a bias? Where does the bias come from, and what makes it untrue? How does this bias not only hurt people around me but ultimately hurt me by preventing the experience of something new?

Racial biases are not the only types of biases. We hold biases about gender, class, nationality and more. And they aren't all necessarily negative as biases in favor of certain attributes exist as well. Positive biases still limit and hurt us and should not be ignored.

Cultural competence, anti-racism and social justice work are not badges we earn and hold onto for the rest of our lives. They are muscles we repeatedly have to flex and work on or they go away. We cannot control our first thought – only our second thought and our first action. What is your second thought today and what is your action?

Peyton Finley is RISE's Manager of Events & Marketing.

Our

Partners

Stay

In Touch

Follow us on social media.